Aging is one of biology’s most universal and mysterious processes. Most living organisms age, although in different ways, yet scientists still don’t fully understand how or why it happens the way it does. Over time, cells accumulate damage and wear down, tissues become less efficient, and the body becomes more vulnerable to diseases and death. But is aging a progressive decline towards death, or does it occur in distinct, identifiable phases? To investigate this, Dr Michael Rera and colleagues at Paris Cité University have been studying aging in model organisms, including the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Read More

Such model organisms allow the team to observe the molecular and physiological changes associated with the aging process in a controlled environment, offering insights into the signs of aging shared across species. This could help us better understand how humans age.

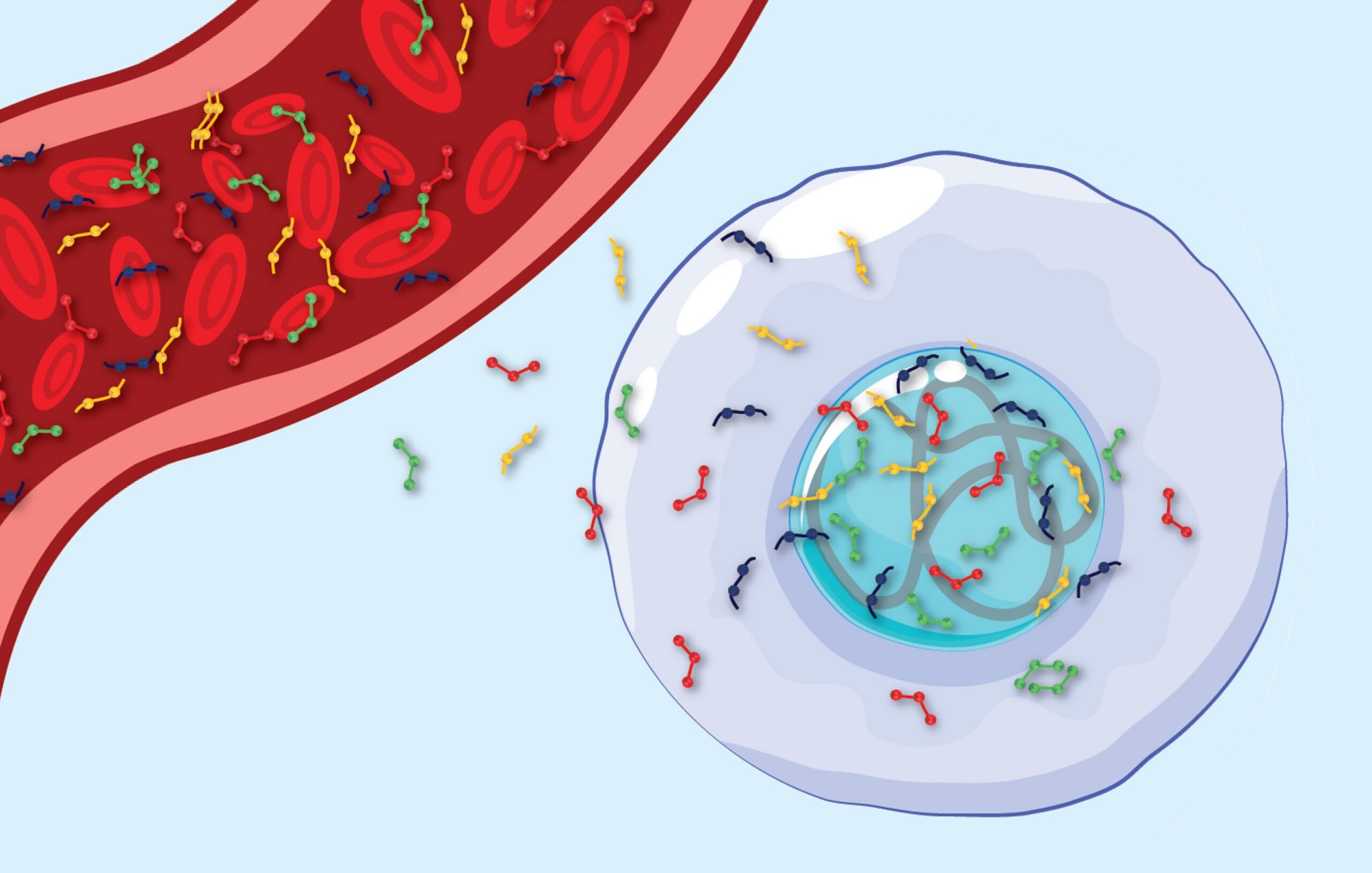

In their research, the team identified a striking physiological change that consistently marked the transition into the final stage of life. This change is characterised by a dramatic increase in intestinal wall permeability in aging flies, which allows a blue food dye to leak from the gut into the rest of the body, turning the flies blue. The team called it the Smurf phenotype.

The loss of intestinal integrity is a symptom of advanced biological age, and it predicts a high risk of impending death from natural causes. Smurf flies, regardless of their calendar age, are far more likely to die within a few days than their non-Smurf counterparts of the same age. This transition is accompanied by other physiological hallmarks of aging – including reduced mobility, increased inflammation, and decreased energy stores. These changes suggest that the Smurf state is not just a single symptom, but instead represents a system-wide collapse.

The findings indicate that instead of being a continuous process, aging is separated into at least two distinct phases. The first is a relatively stable period of gradual changes that mostly affect how accurately cells read and translate genetic instructions. Then, at a critical point – marked by the onset of the Smurf phenotype – the organism enters a second phase, where death becomes highly probable and physiological systems rapidly change in a predictable way. Importantly, this transition is not unique to fruit flies.

Dr Rera and his team tested for Smurf-like symptoms in several other model species, including two other types of fruit fly, a nematode worm, zebrafish and more recently, mice. In each case, they observed the same pattern: a sharp increase in intestinal permeability that predicted a much shorter remaining lifespan, accompanied with a set of so-called age-related markers.

The researchers also found that the proportion of Smurfs in a population increases almost linearly with time – a finding that held true across most studied species. In shorter-lived species, this transition happens earlier and progresses more quickly, while in longer-lived species like zebrafish, it takes longer to unfold. Yet the underlying pattern remains the same. Thus, the alteration of the intestinal barrier (as well as other epithelia) could be a universal marker of advanced physiological age shared across species with stereotypical changes.

Recent studies have also tracked biological age using ‘molecular clocks’, which measure changes in cells and DNA over time. The Smurf model fits this idea well, since Smurfs are much closer to death than non‑Smurfs of the same age. It shows that aging is not just about time passing – it’s also about how the body holds up.

If the Smurf phenotype also predicts the human body entering its final phase of life, it would mark a major breakthrough in aging research and public health, allowing us to better understand age-related diseases. Recent studies published by other teams would suggest so.

By revealing a distinct and measurable turning point in the aging process, Dr Rera’s work offers a powerful new way to study how we grow old – and how we die. It moves the field beyond measuring lifespan alone, toward understanding the progression of organisms through aging, with a quantitative tool linking hallmarks and advanced age. With this knowledge, scientists may one day delay the onset of terminal decline, extend healthy years, and better understand age-related diseases.