What do peaches, cherries, and almonds all have in common? They are all delicious, nutritious, and loved by consumers around the world. They all grow on trees. And all of them may disappear from our supermarket shelves because of a persistent and destructive replant disease called Armillaria or oak root rot. Armillaria root rot is caused by fungi commonly called ‘honey fungi’, because of the golden colour of the mushrooms that sprout from the base of infected trees. However, the mushrooms signal internal devastation for the tree. Read More

The fungal pathogen disrupts water and nutrient flow from the soil to the canopy, ultimately rotting the tree roots from the inside out, and eventually killing the whole tree.

In the Southeast USA, Armillaria root rot causes the loss of around 4% of peach trees every year, costing growers an estimated 8 million dollars. Swathes of cherry orchards in Michigan lie abandoned because of devastating Armillaria infections. In California, more than 12,000 hectares of almond orchards are impacted by the disease.

Growers cannot simply switch to other fruit or nut trees, because of the large number of tree species that the fungus can infect. The fungus can survive for many years in roots in the soil, only to resurface when suitable host trees are planted.

Professor Ksenija Gasic, a peach geneticist and breeder from Clemson University, has assembled a multi-state, multi-disciplinary team of 18 scientists to tackle the Armillaria threat, in order to rescue the stone-fruit and tree-nut industries.

The team consists of geneticists, plant pathologists, economic analysts, statisticians, plant breeders, and others to tackle this complex problem from multiple perspectives. In collaboration with growers, nurseries, and Extension agents, the researchers are developing Armillaria-resistant rootstocks.

The fruiting tree parts that possess desirable characteristics – such as sweet and tasty fruit – are grafted onto these rootstocks so that the resulting trees have the best of both worlds: great fruit above ground and disease-resistance below ground.

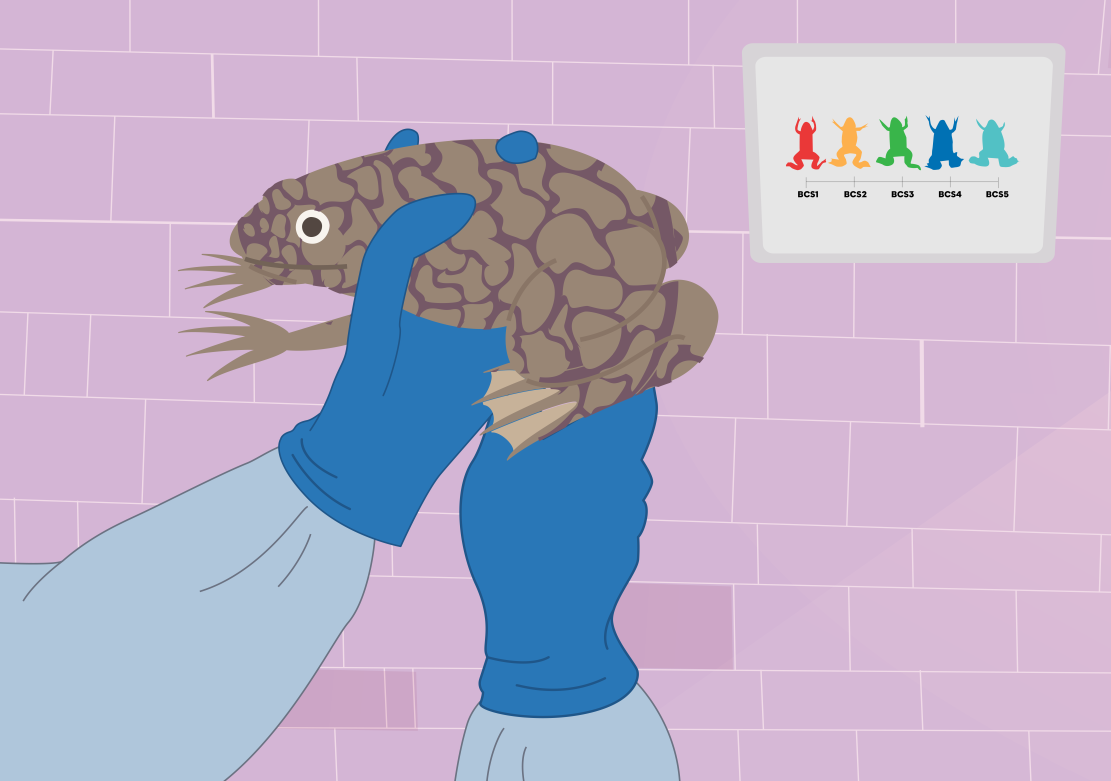

To achieve this goal, a large component of the team’s project has focused on identifying new sources of genetic resistance to Armillaria through laboratory experiments. They test plants from germplasm collections, such as the National Clonal Germplasm Repository, and their recently developed stone-fruit rootstocks for their response to Armillaria fungi. Those that show tolerance in the laboratory are planted in infected fields to confirm their resistance and evaluate rootstock horticultural traits.

Professor Gasic and her collaborators have identified genes and genetic biomarkers that could help them find Armillaria-resistance in other tree species and varieties. These trees can then be used as parents in crosses with peach, cherry and almond, to combine resistance with horticultural performance.

By investigating the resistance mechanisms, such as the production of antifungal substances within root tissues, the researchers are also developing methods to predict resistance. This will accelerate their efforts to develop new resistant rootstocks that will be widely adopted by stone-fruit and tree-nut growers.

Complementing their genetic research, the project team is investigating growing practices that reduce the impact of the disease. They found that the practice of planting trees on ridges and exposing the upper portion of the root system by digging around them – called root collar excavation – increases the lifespan of trees in Armillaria-infected orchards.

Professor Gasic and her team are collaborating with the stone-fruit industry to document the damage caused by Armillaria root rot. The team is sharing their recommendations with peach, cherry and almond growers at regional and local meetings, field demonstrations, and through their project website.