Modern houses are far more than just places of comfort; they are the end products of complex, global processes that are often hidden from view. Professors Mark Jarzombek of MIT and Vikramaditya Prakash of the University of Washington delve into these hidden aspects by studying a modern house built in Seattle in 2018. Their findings reveal that the presumed transparency and simplicity of modern architecture actually obscure deep ethical and environmental issues. Read More

The house at 1119 25th Avenue East in Seattle, with its sleek, modern design, serves as a case study in their book, A House Deconstructed. Although built with sustainability in mind, the house conceals troubling histories tied to the materials used in its construction. Jarzombek and Prakash explore four types of “consciousness” to uncover these hidden stories.

First, atomic consciousness traces the origins of the house’s materials back to cosmic events, such as supernovae that produced the iron in steel beams billions of years ago. This perspective underscores the ancient origins of even the most modern structures.

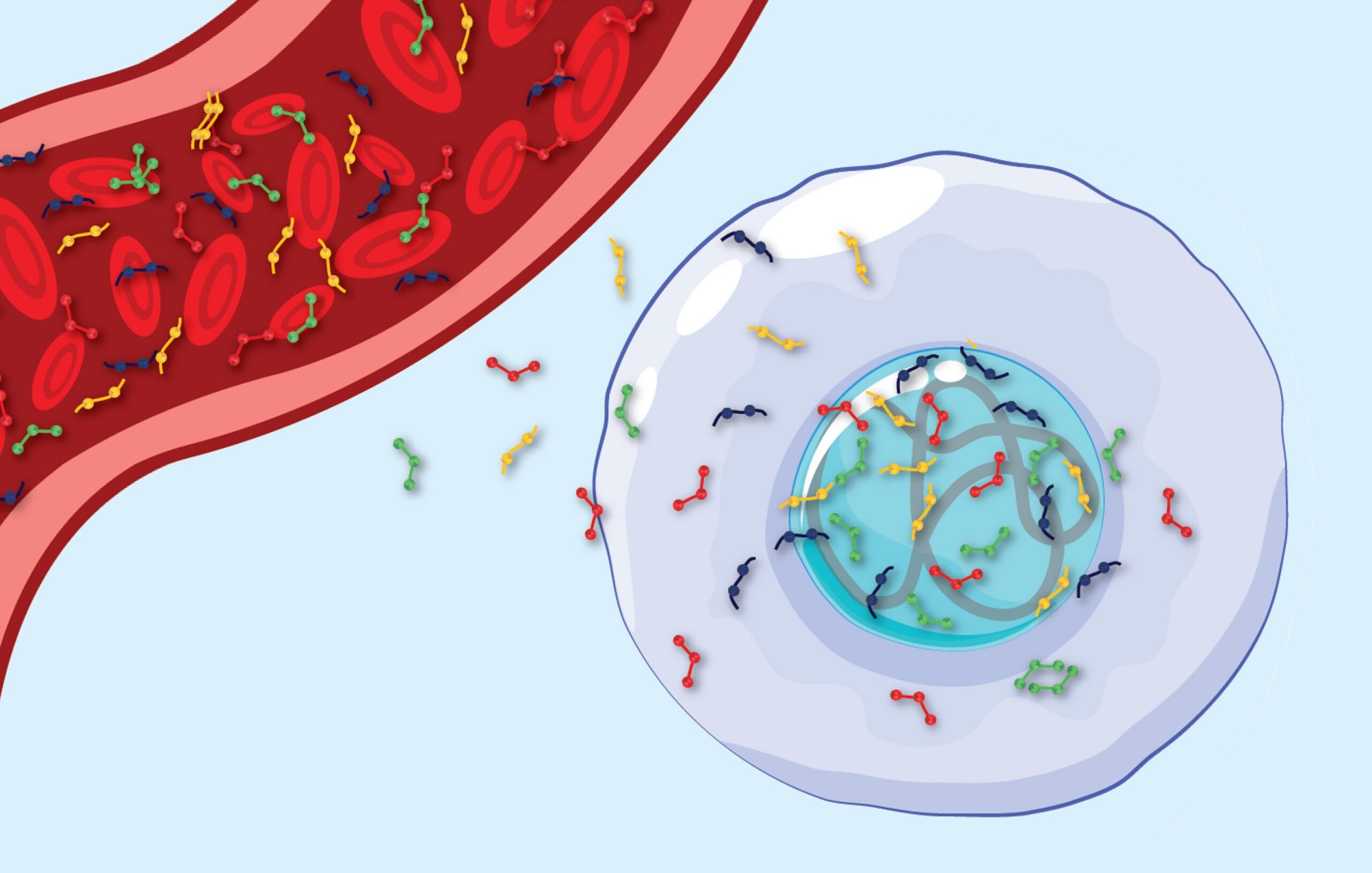

Second, production consciousness examines how raw materials are transformed into building components. Modern construction relies heavily on advanced materials and chemicals, many of which have significant environmental impacts. The steel beams and plastic piping in the Seattle house, for example, involve processes that span multiple continents and industries, some of which are highly polluting.

Third, labour consciousness highlights the global and often overlooked human and non-human labor involved in creating a modern house. From miners in Africa to factory workers in Asia, the construction of each component involves a vast network of labor. Even microorganisms in the soil play a role in the lifecycle of natural materials such as wood.

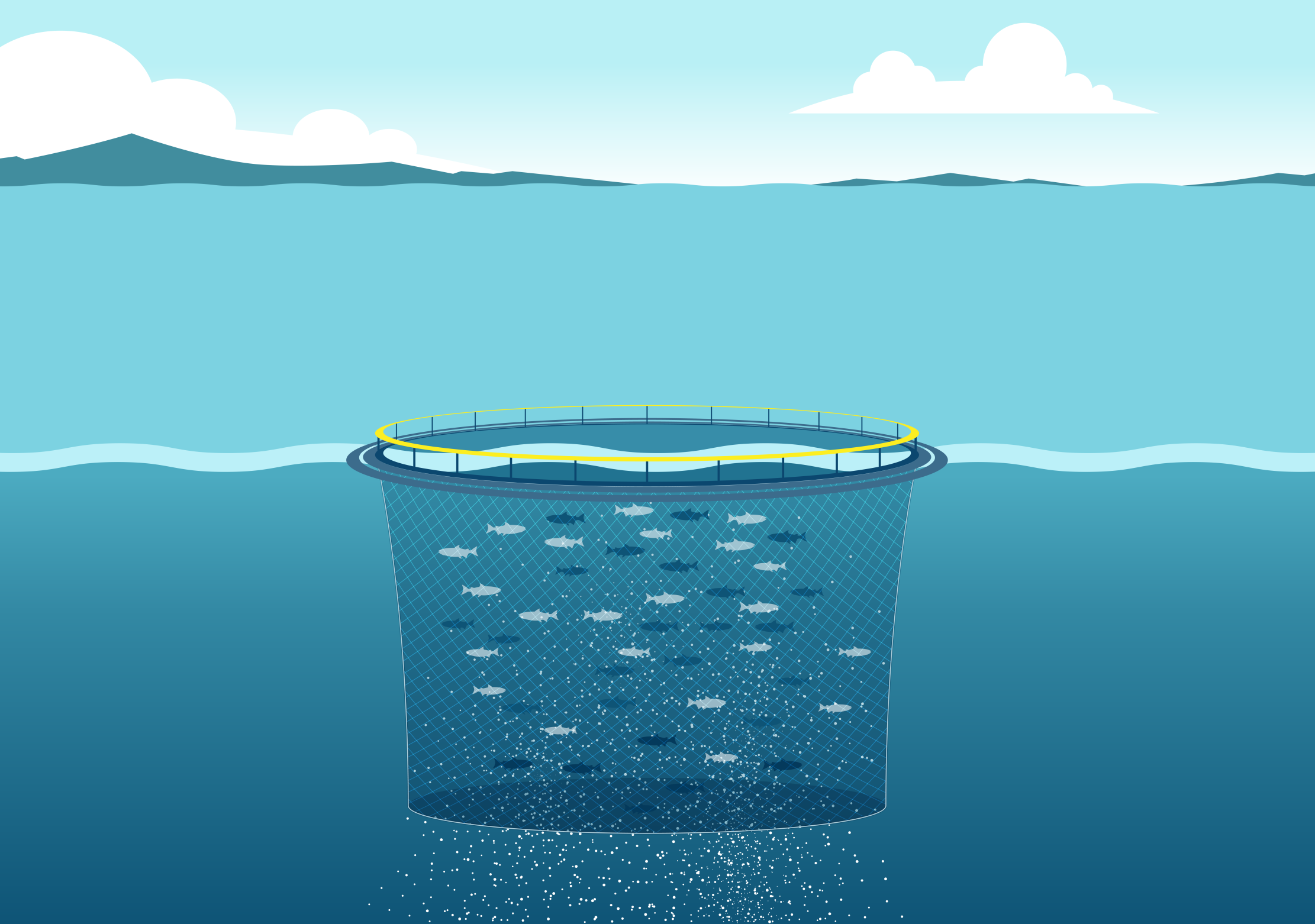

Finally, source consciousness explores the geographical origins of the house’s materials. The global sourcing of materials means that each component has a unique journey, often traveling thousands of miles before reaching the construction site. This raises important questions about sustainability and ethical sourcing.

In one striking example, the researchers reveal that recycled steel used in the Seattle house likely came from an unregulated facility in Bangladesh, where workers are poorly treated, and toxic chemicals are released into the environment. This example highlights the hidden costs of “sustainable” materials.

Through their research, Jarzombek and Prakash call for a critical reassessment of modern architecture, urging greater awareness of the ethical and environmental dimensions of construction. Their work challenges us to consider the profound impacts our architectural practices have on the planet and its inhabitants.